Youth Homelessness, under addressed and devastating

Youth Homelessness affects many within our society and now new pathways must be developed in order to stem the flow of young people entering homelessness.

On any given night, around Australia, 42,000 young people between the ages of 15-24 are without a roof over their head. Between 2001 and 2006 this figure resided itself around 32, 000 people.

This frightful figure was revealed by the National Youth Homelessness Conference - the first in 20 years to focus solely on the issue of homelessness that many young people in Australian face.

Yet, despite the efforts of two landmark reports in 1989 and 2008, youth homelessness has increased immensely in the last ten years.

The issue of youth homelessness has always been one that has plagued the Australian government, so much so that back in 2008 the Rudd Government issued its White Paper. A bold new objective which aimed at halving homelessness by 2020. However, it is now all too clear that the status quo of homelessness programs and services have failed to reduce the numbers of young people experiencing homelessness.

Right now, in Australia, the current specialist homelessness services system consists of 1,500 agencies that offer support and house people seeking help due to homelessness. The system has increased in capacity from 202,500 clients and funding of $383 million in 2008 to 290,300 clients and $989.8 million in 2017-2019.

The 2016 census reported more than 116,000 Australians as homeless, with nearly 28,000 of those being between the ages of 12 and 24. That is almost a quarter of the national homeless population.

The plethora of issues which contribute to a young person becoming homeless is both myriad and complex. Often the circumstances are out of a young person's control and can leave them without a safe place to call home.

Michelle Crawford, CEO of non-profit organisation Concern Australia, says youth homelessness is an issue that has not been adequately addressed.

"There has been a lot of activity in the last ten years that has been focused on addressing the issue of homelessness, but particularly youth homelessness. However, in this period, we have seen a 26% increase in terms of young people experiencing homelessness."

Mrs. Crawford also indicated that 25% of young experiencing homelessness were from Aboriginal or Toristate Islander.

While she acknowledges the endeavours of government and non-profit organisations, she believes there is "a lot more do to".

Many have claimed that the system is failing young homeless Australians.

Fallon Coad a Youth Worker who works with Concern Australian, says youth homelessness needs to be recognised as "a national priority".

"I found it quite disheartening when I came in that this is what we do for our young people in Australia."

Even as young people access state care, they still appear to be at risk.

In a recent study presented by the Salvation Army, it revealed that 35% of young people who access and then leave the system at age 18 become homeless within their first year of leaving.

So, what needs to occur to flatten the curve of Youth Homelessness?

Does the answer lie in a system rethink? Systematical changes that could radically transform Australia's response to such a devastating issue in the next few years.

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) recently released the research report, Redesign of a homelessness service system for young people. The report put together by a team of researchers from Swinburne University and the University of South Australia aimed to provide a system rethink of how we respond to the issue of youth homelessness in Australia.

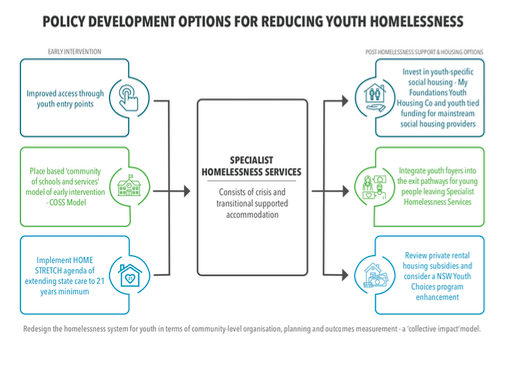

Throughout the report, researchers posed questions about what could be done to stem the flow of young people slipping into homelessness and to disentangle young people from homelessness. Consequently, this led to a reframing of the system in terms of a community level ecosystem of services, programs and supports, organised locally. It is a contrast to the status quo of centrally managed, targeted and siloed programs.

The diagram below, provided by AHURI, outlines a possible road to reducing youth homelessness. Focusing both on early intervention and post-homelessness support and housing options.

A diagram provided by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), which outlines possible roads to reducing numbers around Youth Homelessness. (7 June, 2020).

A diagram provided by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), which outlines possible roads to reducing numbers around Youth Homelessness. (7 June, 2020).

Effective and early interventions are incredibly imperative. A new live in mentor model has been put forth by Concern Australia in order to combat youth homelessness. Concern Australia has implemented this model, in order to provide sustainable support so that young people do not slip into homelessness.

Michelle Crawford, CEO of Concern Australia. Discussing the importance of sustained support when young people have to leave the system.

Michelle Crawford, CEO of Concern Australia. Discussing the importance of sustained support when young people have to leave the system.

This model has the potential to reduce disengagement from schooling and education for supporting at-risk young people.

Along with this model, extending state care and support for young people leaving the care and protection system at 18 years of age is a necessity.

"Having a model that goes through until the age of 21, will allow young people to transition into adulthood in a real supported way." Michelle Crawford talking to the age-limit issue that still affects many young people.

"Having a model that goes through until the age of 21, will allow young people to transition into adulthood in a real supported way." Michelle Crawford talking to the age-limit issue that still affects many young people.

A campaign has been underway to get the various states and territories to extend support until at least the age of 21. Victoria has begun to trail this measure for 250 young people.

Young people on their own are 16% of all specialist homelessness services clients and half of all single clients. But young people only manage to get 2-3% of social housing tenancies. Thus, a rethink of social housing is paramount.

Vulnerable people need continued support, even when they eventually leave the system. A crucial back end measure would be to further develop the youth foyer model in Australia. Foyers provide supported accommodation based on residents' commitment to education, training and employment. In the past decade, some 15 foyers have been developed across Australia.

The set-up of these foyers would not only be a vital part of the homelessness response but allow new tenants to be exclusively selected from young people leaving specialist homelessness services programs. Essentially, giving them the necessary support to carry on with their lives and feel supported every step of the way.

We don't live in a perfect world, far from it. But now as COVID-19 shines a light on all the cracks within our society, significant change is needed. Change that will ensure a better future for generations to come.