Belonging

Finding your cultural identity as a person of mixed-race

The excitement in the auditorium of the Sydney Opera House was thick in the air, as Black icon and singer-songwriter Solange proudly took to the stage.

For Nkechi Anele and Lucie Cutting, this night was like no other. The energy in the space that night was electric, as the singer tore the house down in a proud celebration of Black excellence, creating a place of belonging for all those in attendance.

Nkechi and Lucie at the Solange concert in 2018

Nkechi and Lucie at the Solange concert in 2018

“When I was 13, I took one of those ferries right in front of the Sydney Opera House,” Solange said in the middle of the performance. “And to be here this many years later, and to activate this space, in this way, in such a powerful, moving way, with people from all backgrounds. Lots of beautiful Black and brown people. Lots of beautiful people from all over Australia.”

It was an emotional moment for Nkechi and Lucie, best friends who are both of a multiracial background. Having grown up with Nigerian and Anglo roots and cultures, Nkechi said it had been hard to know where they fitted in, where they really belonged. But this particular night in 2018, with Solange’s performance and the energy of the people that surrounded her and her friend, this is where Nkechi said she felt a true sense of belonging.

"Afterwards, we all stayed in the auditorium and then when they kicked everyone out, there was like, about 100 of us still in there and someone started singing “THIS SHIT IS FOR US!” and everyone, like there’s this African communal sense where everyone started singing it and dancing as we were walking out of the theatre. And that felt like, a sense of inner sanctum belonging, like untouchable belonging. But that being said, I wouldn’t have felt that if Lucie wasn’t there with me.”

Growing up and navigating childhood, then adolescence, is a difficult time in anyone’s life.

The struggles of trying to fit in and feel a sense of belonging weigh down on us, whilst at the same time, we’re trying to figure out who we really are. But how do you find your sense of self and your own identity when you feel like there’s no one who truly understands you? For many third culture kids, that’s exactly how they feel - stuck in the middle or the ‘in-between’, not quite belonging anywhere.

An accomplished radio presenter, musician and social activist, Nkechiyere Anele or Nkechi as she’s known, is no stranger to the limelight. Having fronted Melbourne band Saskwatch for over a decade, her confidence and vitality are clear to all who meet her - but this hasn’t always been the case...

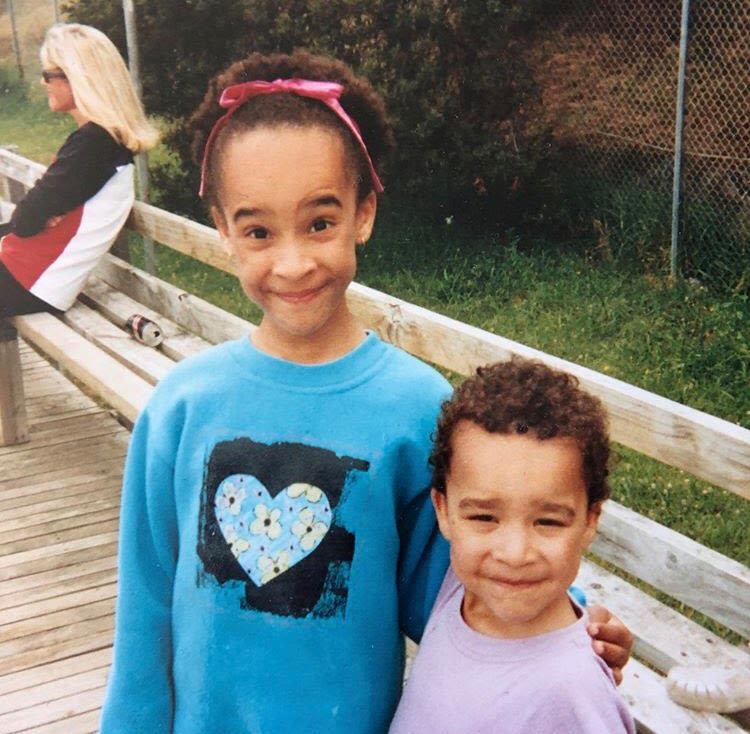

Nkechi Anele and her younger brother as kids, from some time in the 1990's.

Nkechi Anele and her younger brother as kids, from some time in the 1990's.

Nkechi performing on stage with her band, Saskwatch.

Nkechi performing on stage with her band, Saskwatch.

Video footage from Walt Disney Productions, 1941.

Video footage from Walt Disney Productions, 1941.

All over the world, people are used to being categorised according to their skin colour and point of origin. We have this preconceived idea of how each ethnicity should behave and look, yet many white people escape such scrutiny. This can pose confusion for those who are of mixed heritage, who may not necessarily visually represent their background or ethnicity. The Australian Bureau of Statistics records no data in regards to the growing population of people who are of mixed-race, leaving many who identify as bi or multiracial feeling left in limbo.

“The Census does not include a question on nationality, but rather collects data for a variety of other related variables, including Country of Birth and Australian Citizenship. These are single response categories as there should only be one answer,” the ABS says.

Data on ancestry is recorded and therefore the Australian population can be broken down by a variety of cultural diversity-related variables.

However, in comparison to the rest of the world, Australia falls behind, neglecting to acknowledge the nuance that comes with being mixed-race, leaving many feeling marginalised. The United Kingdom began monitoring the population's racial makeup in 1991, and it took 10 years to include categories specific to mixed-race people. This new data revealed in the 2011 census that people who identify as mixed-race are the fastest growing population in the UK, with 1,224,400 people identifying as multiracial.

Over the other side of the pond, the USA started to record data of people belonging to more than one race in the year 2000. According to the PRRI 2019 American Values Atlas Survey, almost 4 per cent of Americans identified with more than one race, which is about three times more than Americans did in 2014. Global statistics show, now more than ever, people who identify as multiracial represent a growing population in many countries.

According to Dr Timothy Kazuo Steains, a lecturer in gender and cultural studies from the University of Sydney, many mixed-race people often feel marginalised by society and are excluded from dominant narratives; for example, by the lack of diversity seen in the media landscape.

“There is this kind of implicit hierarchy I guess where ‘these white lives are the ones that are the most important… so, this is the sort of life that I should emulate' right?" he says.

Dr Steains, of a biracial background himself, says that some people find it easier to just assimilate to whiteness, as over time, they have come to associate their ethnic identity with a “residual feeling of shame”. These feelings are difficult to navigate, especially in youth, when people can often feel different and alone. But by creating connections and talking to people in similar situations, Dr Steains believes that one can begin to fully understand and appreciate their unique identity.

“So just that kind of communal experience of being in the presence of other people and talking about your experiences can be quite cathartic and quite important for someone’s development …for someone’s developing ideas about their cultural identity.”

Compared to 20 years ago, these conversations are gaining traction, slowly making their way into the mainstream - as we’ve seen in recent movements such as ‘Black Lives Matter’, but there is still a long way to go.

Dr Steains says, “creating connections across boundaries of race” through community and association can be integral in shaping one’s identity - and for Nkechi and Lucie, meeting in early adulthood was an important moment of understanding and reassurance.

This prompted a desire to create a platform that could be a resource to those struggling to answer questions around where they’re from, where they belong and to create a space where stories can be shared – just like their friendship.

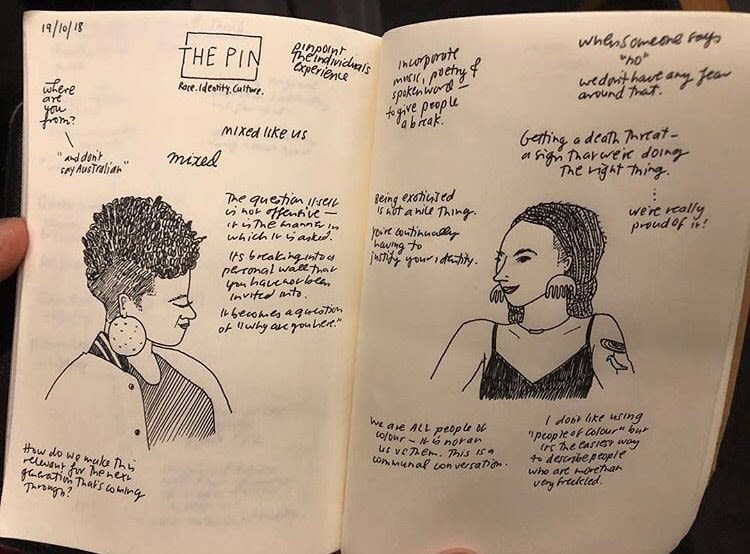

Nkechi and Lucie wanted this organisation to be truly inclusive and label-free, but soon realised their original name for the platform ‘Mixed Like Us’ carried heavy connotations from Australia’s colonialist past.

The term ‘mixed’ is weighted and triggering for many Indigenous people due to the government’s assimilation policies that aimed to “breed out” Aboriginality through genetics. And so, after hitting the drawing board, Lucie came up with ‘The Pin’.

“So, the idea of The Pin was that we were pinpointing the individual to learn from their experience – or like, it wasn’t a sweeping statement about all people of colour or Indigenous or Black Indigenous people of colour in Australia,” says Nkechi. “And we wanted to show that you could have the same background as like ten different people, but your experience is completely unique to you.”

Growing up in a multicultural environment has made Javanese-Indonesian and Anglo-Australian dancer Juliet Burnett hyper-aware of the disparities in the ballet industry - especially for aspiring First Nation dancers. When Juliet announced she was leaving the Australian Ballet company, she was overwhelmed by the number of fans reaching out to her with feelings of being weighed down by the traditional ideals of the art form.

“It was really interesting to note that a lot of people are feeling disenchanted by classical ballet because it doesn’t reflect society nowadays,” she remembers.

Currently, there are only two Aboriginal dancers in the Australian ballet. Despite the company’s efforts with outreach programs for Indigenous communities, they are still bleached with a predominantly white make-up.

“Personally, I think that that’s disgusting. I’m just going to put that out there. I think that that’s really, really terrible. It’s not just the Australian Ballet’s fault, it’s the fault of what white Australia has done to Indigenous people. We’ve deprived them of so much opportunity and equality and they’re marginalised generally speaking and don’t have access to ballet training or whatever other training they want to do. We’ve made it so much harder for them to achieve their dreams and ballet’s just another chapter in that story.”

Evie for the Australian Ballet by Kate Longley

Evie for the Australian Ballet by Kate Longley

Taribelang woman and corps de ballet dancer at the Australian Ballet, Evie Ferris, grew up in far north Queensland in Yidinji country. Her family packed their bags and relocated to Melbourne 10 years ago to pursue her dream of becoming a ballet dancer.

“I feel like I’ve definitely faced challenges when people kind of undermine my abilities, my talent and my work ethic and put it down to having a token aboriginal person (in the company). Like, I’ve had remarks being made I’ll get employed because it ticks a box for a company, “says Evie.

With her long delicate limbs and perfectly arched feet, there is no doubt that she has earned her place on the stage. Evie inherited her mother's lighter skin, which has prompted questions from others about 'what percentage?" Aboriginal she is and why she identifies as a First Nation person.

The world is filled with diverse people, from all walks of life. Every single person has their own story to tell, their own unique experience that has shaped who they have become.

Platforms where personal stories are shared and archived like ‘The Pin’, are crucial to assure people a sense of community, connection and ultimately a sense of self.

Family, friends, environment and societal pressures all sculpt us as we move through life - but ultimately, to fully embrace oneself, it’s about learning to acknowledge and share the beauty in our individuality.

So, how should you celebrate your cultural identity? How should you embrace all the cultural nuances and complexities that make you who you are?

“However the fuck you want to,” says Nkechi. It’s yours. Culture only exists because it’s passed down through peple and practices and there is no wrong or right way to experience it. And you should never feel bad for picking and choosing what you like about it and taking that with you and practicing that. No one has the right to tell you how to express your culture.”