Battling Bias Through Books

How diversity in children's stories can tackle problems before they appear

Source: ILF and Wayne Quilliam

Source: ILF and Wayne Quilliam

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge and pay respects to the Wurundjeri people, the Traditional Custodians of the unceded land on which this article was written.

We would like to pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging, and acknowledge all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders reading the article, also paying our respects to your Elders, past, present and emerging.

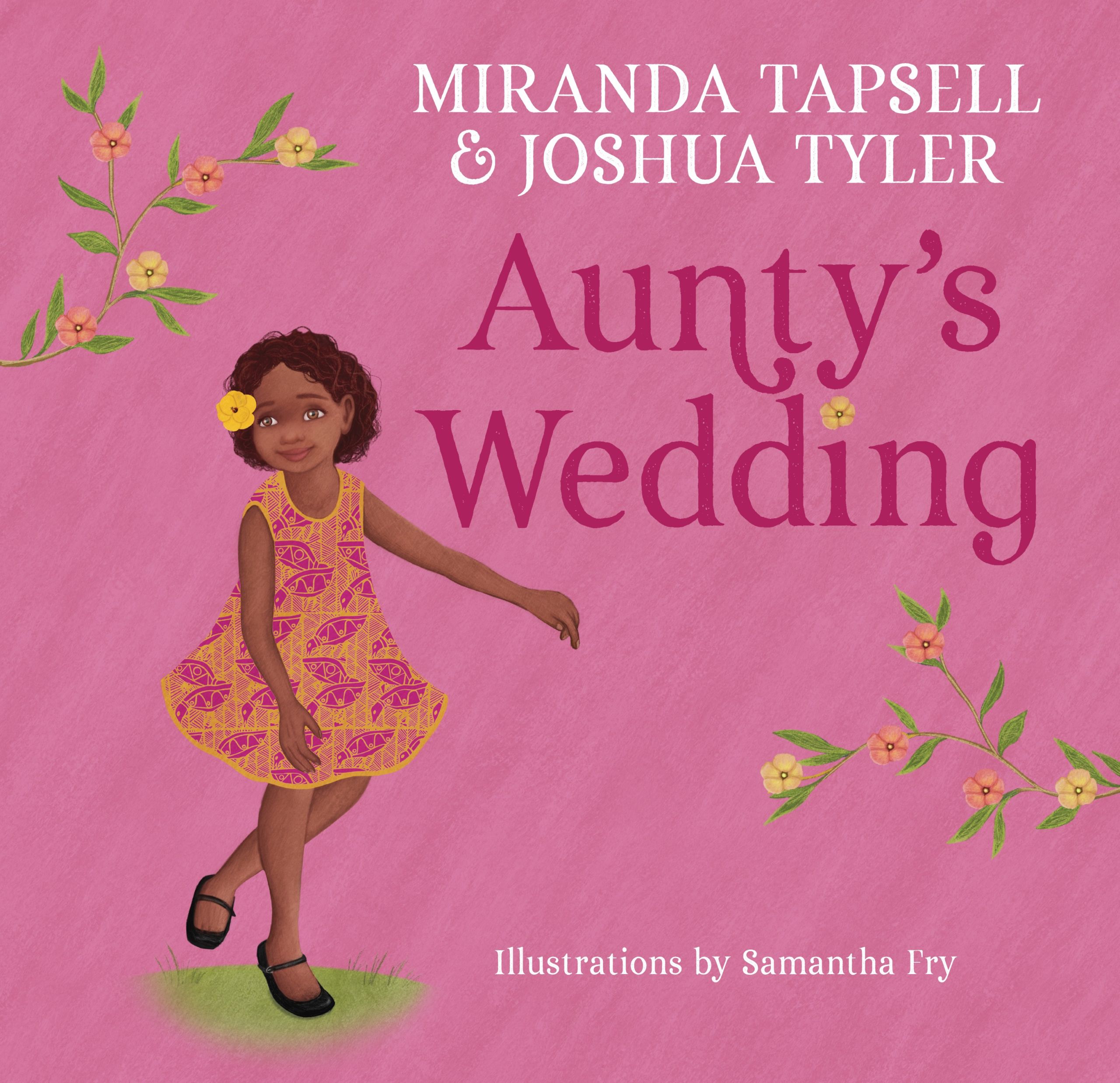

Screenwriter and author Joshua Tyler published his first children’s book Aunty’s Wedding in early September this year. Co-written by Australian Aboriginal actress Miranda Tapsell, the story celebrates Indigenous Australian culture in modern settings, aimed at children.

The beautiful story has come at a time where there has been a massive push for diverse children’s content.

Experts say children's books are crucial to promoting inclusion and breaking down bias against Indigenous cultures at an early age.

Jonathon Magrath and Patrick Gabriel report on the impact of diversity and representation in children’s books in Australia.

In May this year, the world was once again reminded of the weight and impact of systematic racism and oppression through the death of black man George Floyd in the U.S at the hands of a white police officer in the U.S.

Americans marched for the Black Lives Matter movement. The rest of the world did too.

Largely through social media, calls were made to reconsider the way we live our lives. From perpetuating racial discrimination, to having uncomfortable conversations to uncover truths we may have not previously acknowledged-- stones were being turned.

Google data shows spikes in the search terms 'Aboriginal Australians' and 'Black Lives Matter' earlier this year.

The ongoing conversation in this country involves education and dialogue around Indigenous Australian culture as well as examining our treatment of First Nations people.

While uncovering this information is important and relevant at any stage of life, children naturally are rarely exposed to the full brunt of the conversation.

It is in picture storybooks and youth-based texts though, that the discussion is able to begin.

In looking at the texts and ideas presented to children in the school environment or around the home, we are able to see how personalities and ideas are formed and nurtured.

Joshua Tyler believes it is important to provide realistic and modern reflections of the communities that live in and around our nation.

Focusing on collaboration with established and informed voices, Joshua’s work with Miranda Tapsell- an actress and descendant of the Larrakia people- explores the importance of contemporary portrayals of Indigenous Australian communities, and how considered and relevant interpretations can be presented to children.

Joshua Tyler and Miranda Tapsell at the ADL Film Festival Source: Joshua Tyler

Joshua Tyler and Miranda Tapsell at the ADL Film Festival Source: Joshua Tyler

As a prominent author, playwright and screenwriter in Australia, Joshua Tyler leans heavily on the information, and lack thereof, he was afforded when growing up. As a non-Indigenous Australian man growing up in the Barossa Valley, on Peramangk country, Joshua observed the education system’s portrayal of Indigenous Australians and the inflexible lens they were acknowledged through.

In understanding the impact early education can have on the formation of ideas about race, diversity and culture, Joshua’s most recent works attempt to provide a contemporary discussion about the plethora of cultures associated with Indigenous Australians.

More importantly though, Joshua’s work celebrates the often times neglected similarities between cultures in the nation, providing a mainstream text that is far more reflective of modern-day Australia than the history books responsible for alienating so many people in the past.

Joshua previously collaborated with Miranda Tapsell on the film Top End Wedding, released in 2019.

The film follows Lauren (Miranda Tapsell) and the lead up to her wedding, while also taking audiences through the Tiwi Islands as she attempts to find her mother who has gone missing before the big day. The uplifting film received multiple award nominations from the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts, Australian Film Critics Association Awards and the Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards.

Their most recent work, Aunty's Wedding, builds off this story and caters more to a child’s perspective.

This story follows a Tiwi Island girl preparing for her aunt’s wedding and examines how love is celebrated in similar and different ways through one specific Indigenous Australian community.

The book was brought to life by celebrated Indigenous Australian illustrator Samantha Fry and published by Allen & Unwin.

Cover of Aunty's Wedding Source: Allen & Unwin Book Publishers

Cover of Aunty's Wedding Source: Allen & Unwin Book Publishers

At the heart of both of these stories, Joshua tried to reflect on practices familiar to everyone and celebrate the unique differences that modern Australia should be proud to encompass.

Presenting content that celebrates the multiple cultural similarities and differences in the nation does come with its own set of responsibilities though.

Joshua notes that he would never have thought or even considered writing the film or book alone, acknowledging that collaboration and insight from Miranda Tapsell and other colleagues, who have a “lived experience” as Indigenous Australians, was the only responsible process in which to author a text such as this.

“Co-writing it was the only way to do it and the right way to do it, it’s the better way to do it”.

In terms of audience, Joshua explained some important things he considered when shifting his focus from adult-based content to child-based.

With the film and book being based in the Tiwi Islands, plenty of local language is included. The inclusion of this helps paint a realistic picture of the location and celebrates one of the many, many Indigenous Australian languages spoken across the country.

Joshua outlined the importance of this choice as well, which was necessary in assuring authentic representation was captured.

In creating both of these incredibly rich and diverse texts, Joshua and Miranda are just an example of the manner in which current authors, actors, screenwriters and other creators are leading the way in terms of representation and diversity regarding Indigenous Australian people and practices.

Presenting diverse cultures in the mainstream sphere has never been more important than right now, and is the right step to take in terms of normalising differing lifestyles and reducing the prevalence of prejudice and bias at the earliest stages in life.

Joshua extends on this by saying having children of his own has allowed him to understand how intelligent and inquisitive younger minds can be, which highlights the need to tell stories as accurately and informatively as possible.

With the work and efforts of people such as Joshua Tyler and Miranda Tapsell reaching audiences in new and realistic ways, consideration must also be paid to the foundations and organisations that use the content to do their bit in the actualising of a better tomorrow.

Source: Wayne Quilliam and ILF

Source: Wayne Quilliam and ILF

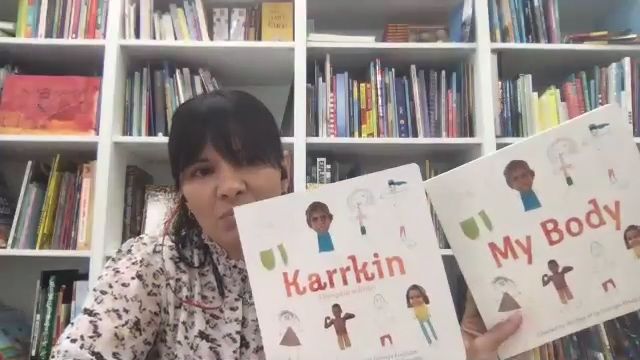

Tina Raye is the program director of the Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF). She belongs to the Bardi and Jabirr Jabirr and Arabana people and says there have been advancements in books being available for and relevant to Indigenous communities.

ILF Program Director Tina Raye holds 'Karrkin' (My Body). The book has been translated into the 5 different languages spoken in the Bidyadanga community

ILF Program Director Tina Raye holds 'Karrkin' (My Body). The book has been translated into the 5 different languages spoken in the Bidyadanga community

“I’ve been with ILF for seven-and-a-half years and I've probably purchased over 500,000 books. I’ve seen a lot and we’ve seen a huge growth in Indigenous content out there,” she said.

“I think books are done in a more culturally appropriate way. It’s much more important when Indigenous people are involved in the storytelling process.”

Tina spoke about the work ILF is doing to bring books to remote communities.

Tina says the most important part about providing books to Indigenous children is engaging them in the story. Children are not interested in stories if they are not relevant to them.

The settings, the characters and even the languages in the stories impact whether or not children will want to read them, and the lack of Indigenous content puts Indigenous children at a disadvantage from an early age.

“How to hold a book, turn a page, knowing what a letter is … when we are in cities or grow up with books around us we organically get those skills, but for a lot of kids in remote communities where they don’t have books, and books aren’t a part of their lives, they’re already starting school behind,” Tina said.

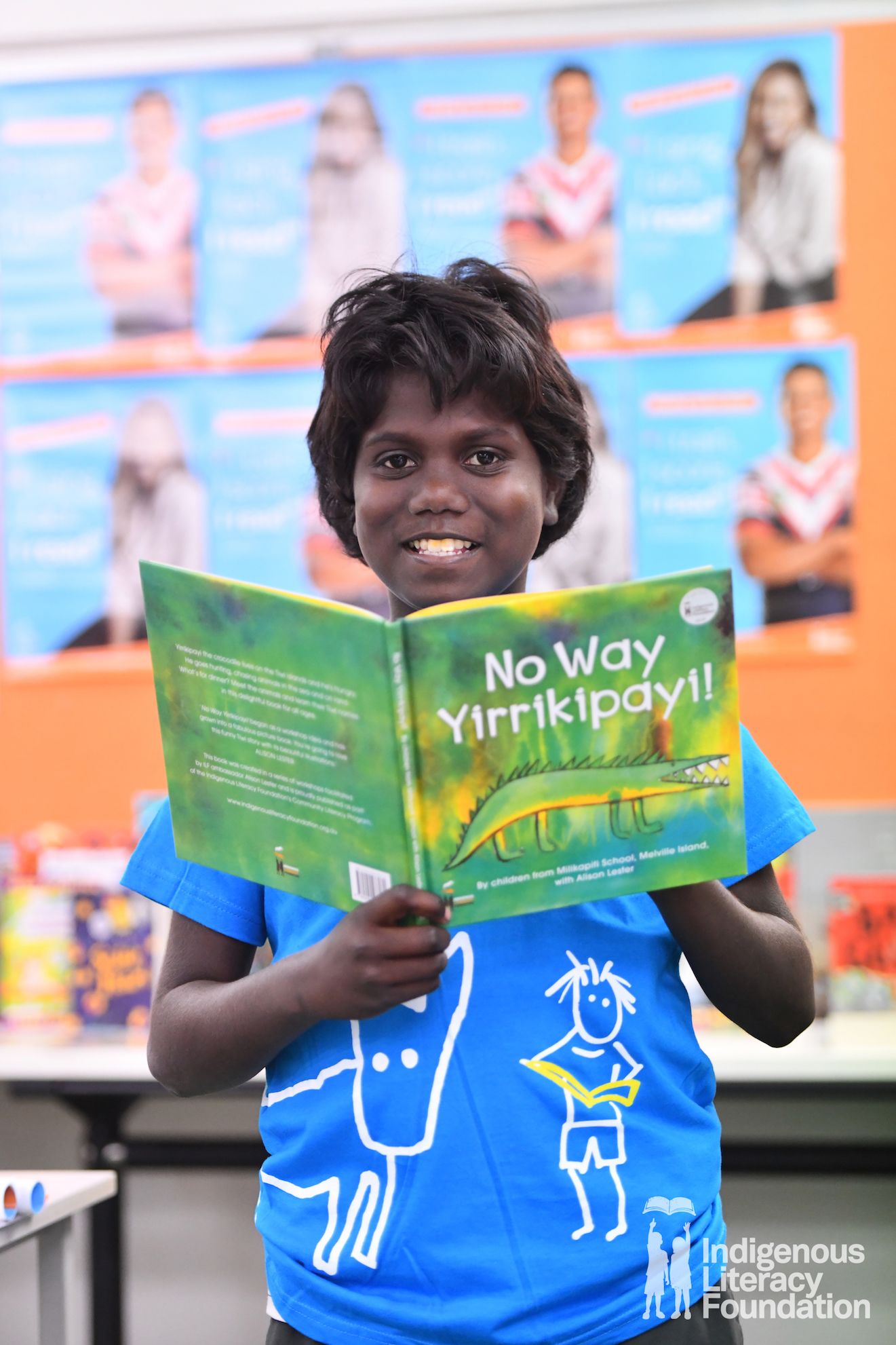

Allowing children in remote communities access to books is the biggest part of ILF’s work. This year, ILF gifted over 98,000 books to remote Indigenous communities. Tina said they’ve never had such a strong interest.

ILF has supported communities to translate books into about 10 different Indigenous languages. Mainstream classics such as The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Dear Zoo, and Where’s Spot have all been translated. There are over 250 different Indigenous languages in Australia, and Tina says the more children can read in their own language, the more engaged they will be with the book.

“If you flip that and go for mainstream non-Indigenous kids, if we only expose them to French, are you going to get kids interested in reading if they're reading a language they’re not familiar with? I think it's really important that kids can identify themselves in books and it’s something that’s really been lacking.”

Tina believes it is empowering for Indigenous children to see themselves in the books they read.

“I've seen research particularly for girls, often they think that if they've got brown skin or dark coloured eyes or dark hair that they're not pretty because they don't often see that in posters or books or in TV. It’s validating,” she said.

“People look all different ways and I think that's something we should be celebrating or recognising a lot more. Naturally, that is happening but I think it needs to happen more.”

The ILF recently had its annual Indigenous Literacy Day in early September. Forced to go online due to COVID-19, Tina said the virtual event had a far greater reach and more people participated in the events. Guest speakers such as actress and children's entertainer Justine Clarke and author Andy Griffiths were featured and a highlight was Jessica Mauboy singing the ‘Barramundi Song’ in Tiwi and Mangarrayi, spoken in northern Australia.

Tina said the song was a fantastic way for children to engage with and celebrate Indigenous languages.

Source: Wayne Quilliam and ILF

Source: Wayne Quilliam and ILF

Having more Indigenous books available for remote communities, as well as diversifying characters and themes in mainstream children’s books, will help Australia break down its unconscious bias against Indigenous Australians.

Course coordinator for the Master of Teaching (Primary) at Edith Cown University Dr Helen Adam says there has been a push towards more diverse children’s content, but the progress has been slow.

Dr Helen Adam is a Senior Lecturer and researcher at Edith Cowan University

Dr Helen Adam is a Senior Lecturer and researcher at Edith Cowan University

“I think that everything that's happened this year with COVID and Black Lives Matter movement, what's happening is a lot of people are taking a lot more interest and realising that these calls for diverse books and diversity and how our curriculum is structured and placed,” she said.

“We’re seeing that publishing houses and bookshops that publish and sell books by First Nation authors or minority authors are experiencing a greater interest in those books which is a fantastic thing and it's a shame it's taken tragedies like that to garner more awareness.”

Research shows that 75 per cent of Australians hold an implicit bias against Indigenous Australians, unconsciously seeing them negatively.

A study conducted last year by Dr Helen Adam showed that only 10 per cent of books across five early education centres in Western Australia contained non-Caucasian characters. Only 2 per cent of books had any Indigenous content and 1 per cent of these books were shared with children. Of 221 books observed in the study, 20 per cent contained cultural diversity, however many of the views were outdated.

With 25 per cent of Australians coming from minority backgrounds, Dr Adam says it’s disappointing the majority of children’s books are from monocultural viewpoints.

“Children develop their sense of identity, their sense of understanding themselves and others that are different from them from a very early age,” Dr Adam said.

Source: ILF and Wayne Quilliam

Source: ILF and Wayne Quilliam

Dr Adam said books are dominated by white messages and white heroes, which can be damaging to minority groups. She said sharing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories in mainstream communities helps empower Aboriginal children and break down stereotypes and biases.

Dr Adam urges parents to look at what is on their children's bookshelves and think about how much representation of diversity in our society is in those books.

“They don’t have to be stories about race and struggle and hardships, just ordinary everyday books,” she said.

“All children should be able to pick up a book that's a rollicking good book that has people just like them in it.”

For Australia to overcome its Indigenous biases, focusing on the next generation is key.

If children grow up surrounded by diverse material that represents our diverse society, it’s clear we can move towards a more inclusive multicultural nation.